Context Engineering in the Wild

Real-world lessons from building a browser-use agent.

I've been hacking on a browser-use agent that resides inside a frontend component. The idea is to allow applications to ship browser-use assistants to their users in their current browsers1. In the process of making it, there were a lot of learnings about building agents, specifically around context engineering.

tldr

- A simple harness and a lot of context engineering can make a powerful agent.

- Coding agents are not the best for every use case. Each workflow has its own optimal way of structuring context in the prompt.

- A method for context engineering - pretend you're the model, look at the logs, and predict the next response. Tweak until you have just the right amount of information in the context to make good responses.

Harness

The harness in this component was similar to actual browser-use agents like Stagehand and ChatGPT Atlas. At its core, it's a loop that calls the model with the message history and current page, and runs the UI manipulation tools it returns:

while(not is_complete):

tools, is_complete = call_llm(message_history)

run_tools(tools) # e.g., click button_42

dom = get_page_dom()

message_history.update(tools, dom)

dom has unique identifiers for each UI element, and the model responds with tool calls that apply actions such as clicking or form filling to elements.

Context Engineering

With the same harness, the agent went from completely broken to pretty impressive. All it took was tweaking the contents of the message_history, i.e., context engineering.

I'll share how the message history structure naturally evolved in the course of my development and lessons from each stage.

First, a quick note on my development process.

To debug agent behavior, I looked at the logs, pretended I was the model, and tried to predict the next response. When the logs didn't have the information I needed to make a good response, I added that into the context for the next iteration. Similarly, I removed any irrelevant stuff. This simple debugging process was surprisingly effective!

For each iteration, I ran a test for the agent - post all transactions related to Gusto in QuickBooks Online2. A transaction is posted by clicking the "Post" button in its row, after which it disappears from the DOM.

1 - Action and DOMs

After some initial experimentation, the message structure that seemed to work was:

message_history = [

{ system prompt },

{ user query },

{ turn 1 - tools called },

...

{ turn N-1 - tools called },

{ current page DOM }

]

The system prompt contains instructions of what the model is expected to do - a detailed version of "You're a browser-use agent, here are your tools, help the user achieve their goals.". The user query is the input that the user provided, in this case a request to post all Gusto transactions.

The DOM at the end gives the model an understanding of the web app's current state. The chronological history of tools called in past turns informs the model about what steps it's already taken so it doesn't repeat them (not providing this history led to a lot of repeated actions).

With this context, the agent managed to post the Gusto transactions, but did not end its turn after that. After posting the transactions, it kept trying to locate unposted Gusto transactions. The model could only look at the current DOM, so it had no idea about whether/how its past actions had affected the app's state.

2 - Actions and Last Two DOMs

I provided the past two DOMs, so the model could see how its last action modified the app's state.

message_history = [

{ system prompt },

{ user query },

{ turn 1 - tools called },

...

{ turn N-2 - tools called },

{ turn N-1 - page DOM },

{ turn N-1 - tools called }

{ current page DOM }

]

This was the first time I felt like the agent was alive! It managed to post the Gusto transactions, then checked the posted transactions to confirm they were posted, and then ended its turn.

In my test case, the model only needed to understand the effects of its last action on the app's state, since the transactions disappear from the DOM after posting. Providing the last two DOMs was just enough for this test case to pass.

3 - Actions, Screenshots, and DOMs

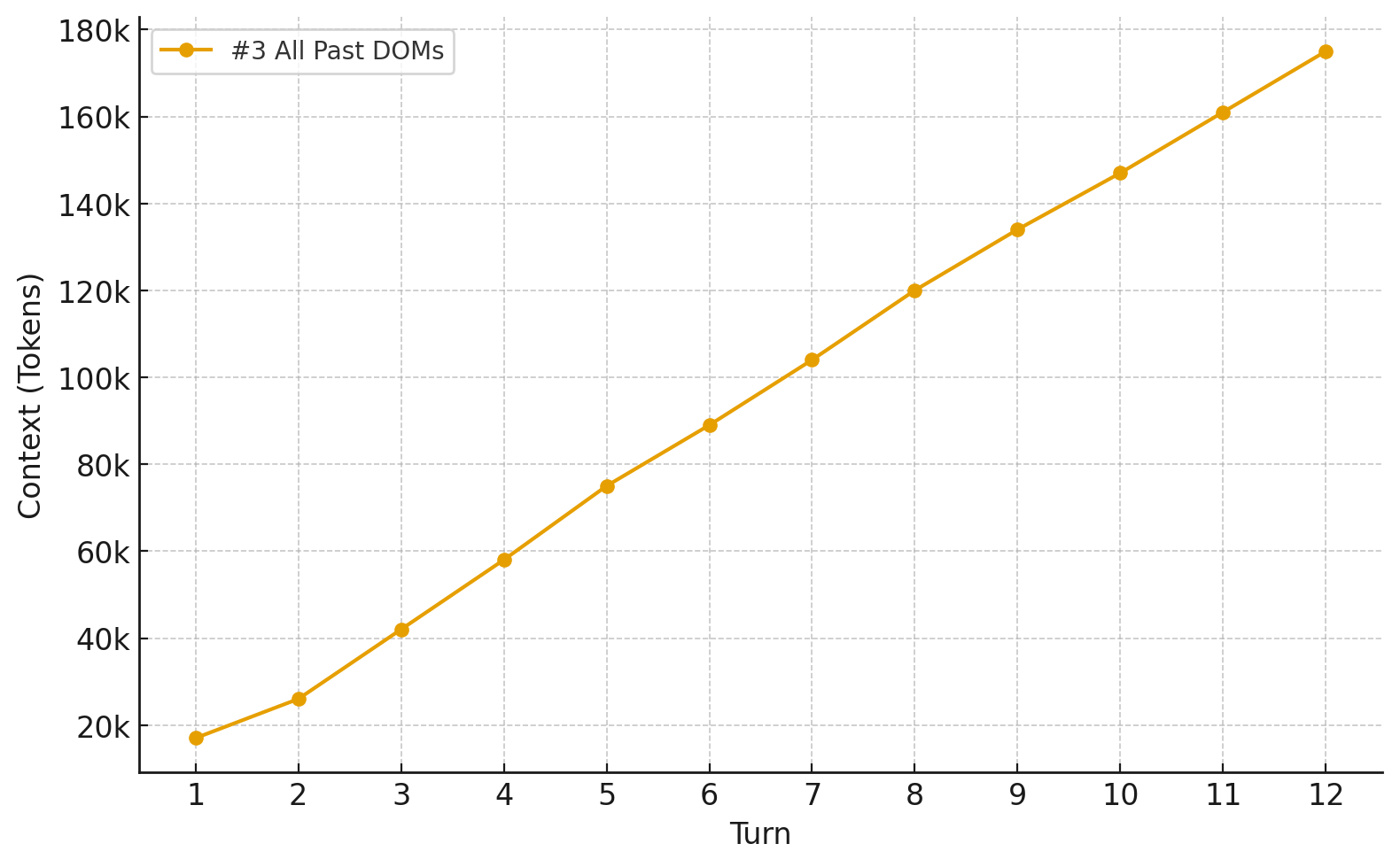

I wanted this agent to handle longer tasks, which could potentially span across multiple pages. The model would need to remember parts of the app's state from multiple pages. An easy way to provide this is to give the page DOMs for all past turns, like we did with past tool calls. Page screenshots are another representation of the app's state, so I added that too.

message_history = [

{ system prompt },

{ user query },

{ turn 1 - page screenshot },

{ turn 1 - page DOM },

{ turn 1 - tools called },

...

{ turn N-1 - page screenshot },

{ turn N-1 - page DOM },

{ turn N-1 - tools called },

{ current screenshot },

{ current page DOM }

]

This worked great - passed my test case with ease.

This approach is how coding agents operate a browser MCP, e.g. using Claude Code with the Chrome DevTools MCP.

It runs into a problem though - each turn shovels an enormous amount of tokens into the context window.

4 - Actions, Screenshots, and Last Two DOMs

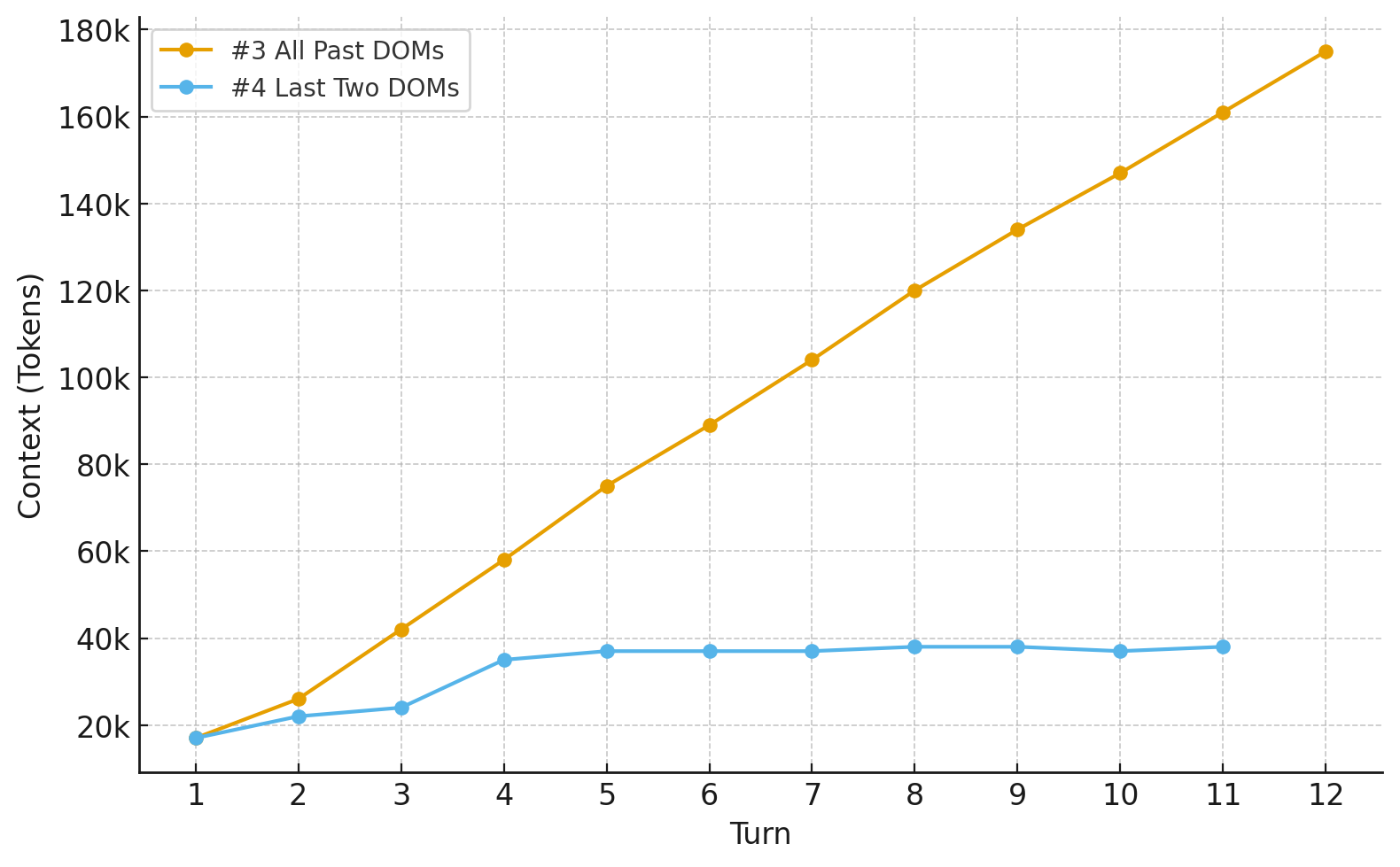

I dialed back the context growth by giving it the DOMs for only the last two turns. The past two DOMs show how the last action changed the DOM state of the current page, which helps plan the next action. For turns beyond the past two, the most important thing to preserve is the app's state from those pages, which can be inferred from the screenshots.

message_history = [

{ system prompt },

{ user query },

{ turn 1 - page screenshot },

{ turn 1 - tools called },

...

{ turn N-2 - page screenshot },

{ turn N-2 - tools called },

{ turn N-1 - page screenshot },

{ turn N-1 - page DOM },

{ turn N-1 - tools called },

{ current screenshot },

{ current page DOM }

]

That did the trick! Context managed.

The agent now completes a surprising breadth of tasks with this relatively simple harness and some context engineering.

Other Notes

There's a lot of room for improvement. Todo management systems like coding agents can help with longer/complex tasks. Oh, and instead of using a singular test case, this should be evaluated against a meaningful browser-use benchmark.

Footnotes

-

Browser-use agent is a misnomer for this component - it'd only ever work in that application's frontend. ↩

-

I wanted to test on a real website, so I injected the frontend component with a browser extension. It was my real QuickBooks account, so I was eagerly reading the console logs to close the window before any irreversible bad action was executed. ↩